Dockless: Exploring the fastest growing sector of the sharing economy

By cameron in Uncategorized

Chinese technology companies are often accused of being knockoffs of American firms, but Silicon Valley startup LimeBike’s recent 50 million Series B round shows that the copycat model can apply in the reverse direction as well.

Based in San Mateo, California, LimeBike has become the largest American company in the booming dockless bike share space. Despite having only been founded earlier this year, its recent fundraising round puts its market valuation at $225 million.

It’s not surprising that American companies and investors are keen for a piece of the dockless pie after seeing the concept’s success in China, which is home to not just one, but two dockless bike share unicorns.

Ofo goes global

Beijing-based Ofo has an estimated market valuation of at least $2 billion following a $700 million Series E investment led by Alibaba Group earlier this summer, and recent rumors suggest that it’s looking to merge with fellow Beijing startup MoBike, the second biggest player in the space, which recently just completed a $600 million round of funding itself.

These mammoth rounds of funding make this the fastest growing segment of the sharing economy. How did dockless get become so hot — and what are the implications for the travel industry?

The dockless revolution

The American bike-share market has boomed in just the past few months with notable rollouts in major cities including Seattle, where it’s being used to replace the defunct Pronto system, and Washington DC, where it will coexist alongside the already popular Capital Bikeshare system.

The dockless concept is of particular interest to the travel community, especially cities who need to navigate the opportunities and challenges posed by such systems compared with other options.

While many cities welcome bike share as a means to decrease traffic congestion and improve quality of life, traditional bike share systems such as New York’s CitiBike have allowed cities to maintain control over where the bikes themselves get parked.

With dockless bike share, that becomes crowdsourced, with complaints of illegally-parked bikes clogging up sidewalks seemingly causing headaches for local governments everywhere from Melbourne to London.

The somewhat “rogue” nature of dockless bike share itself hasn’t been helped by what’s been perceived as rogue behavior by many companies in the space. In San Diego, Ofo ruffled feathers when it rolled out on the UCSD campus without final approval from the school. Bluegogo, yet another Chinese bicycle startup, attempted to launch in San Francisco this past January, apparently without discussing its plan to do so with any local city officials.

And after numerous regulatory battles with disruptive hometown startups such as Uber and Airbnb, it’s not surprising that the city did not respond kindly. “I am done with tech companies that disrupt and then ask for permission and/or forgiveness after the fact. That chapter of San Francisco history closed today,” declared San Francisco Supervisor Aaron Peskin after Bluegogo’s failed launch.

Perhaps seizing on these public relations mishaps by their larger, foreign rivals, American bicycle share companies are attempting to distance themselves from that rogue label specifically by being more proactive with community leaders.

Lime Bike recently raised $50 million

Speaking to tnooz about what makes them different from their competitors, LimeBike VP of Marketing & Partnerships Caen Contee states that:

“We work very closely with our city partners to design a dockless bike share system that works,” noting that this collaborative approach has won them accolades by organizations such as the Smart Cities Council.

Can dockless actually work?

Other cities have been much more welcoming of dockless bicycle share, specifically because of its perceived low risk and minimal cost.

In August, Seattle became the first major US city to embrace dockless when it granted permits to several dockless firms to operate in the city, seeking to fill the void left by the demise of its own Pronto system earlier this year.

Launched as a non-profit in 2014, Pronto struggled with ridership and revenues and was purchased by the city in 2016, before finally being shut down this past March. Seattle has essentially allowed a private, for-profit marketplace to step in where a non-profit and publicly-funded system had previously failed.

The turnkey nature of dockless bike share has meant that its popularity has extended well beyond large cities. The model has proven to be a hit on college campuses, as well as smaller communities.

LimeBike recently completed a temporary pilot program in South Lake Tahoe, California for the summer season. Although its presence did upset some of the local bike rental shops, LimeBike says that the program will resume in April once winter is over.

This ability to roll out and roll back the system as need and seasonality allow stands in sharp contrast to systems like Boston’s Hubway, which used to shut down during the snowy winter months.

One of the tough sells for cities with traditional bike share docks is that they take away precious parking spaces. When those parking spaces are being taken away for several months for a bike share system that isn’t even operational during those months, that becomes a much tougher sell.

For other cities, the appeal of dockless bike share stems specifically from not needing to manage the system, not needing to install and maintain the infrastructure, and perhaps more importantly, not needing to pay for it.

Whereas Seattle welcomed dockless bike share as a replacement for its failed dock-based system, Dallas officials noted that the high cost of traditional bike share was precisely what had prevented the city from ever getting a program going beforehand.

Bad behavior

While the dockless model allows private enterprise to assume financial responsibility for a city’s bike share system, ceding public streets to private companies is something that has riled many transportation advocates.

Other criticisms include the fact that bikes often wind up abandoned on city streets when firms shut down or skip town. And with dockless bike share being so dependent on courteous behavior by its users, some have questioned why consumers should ever be entrusted with such responsibility in the first place.

Back in China, inconsiderately parked dockless bikes are causing locals to question both their own national character as well as human nature in general.

With traditional bike share, users who fail to return their bike to the docks are hit with a hefty fine. The fee for not returning a CitiBike in New York is a whopping $1200. This mitigates most risk of the bikes being dumped in the Hudson River.

With dockless, users are advised that they should park in certain areas and not park in others, but there’s no way for the operating companies to enforce this on the users themselves, so bikes inevitably end up wherever users are willing to ride them.

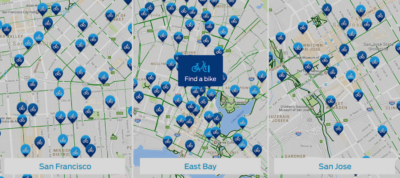

In the Bay Area, LimeBikes are showing up as far south as San Jose, despite the fact that the company is only authorized to operate in South San Francisco and Alameda, each of which is 40 miles away.

As all dockless bikes are GPS-enabled, the operating companies theoretically should know where they all are and would seem not to benefit from them drifting too far astray.

“Any bike that’s sitting unused represents lost revenue for our company,” claims Derrick Ko, CEO and co-founder of Spin, a San Francisco startup which secured $8M in series A funding in May and which now competes against LimeBike and Ofo in Seattle, Dallas and Washington DC.

Both Spin and LimeBike told tnooz that although their terms of service indicate that bikes need to be returned within a certain service area, they currently have no plans to penalize users who fail to do so.

That inevitably means bikes not being returned to those designated service areas, as was the case in July, when LimeBikes from Key Biscayne began showing up in nearby Miami Beach. Displeased Miami Beach officials threatened the company with fines of $1000 for any bike left within its city limits, as well as remind them that CitiBike (not to be confused with the New York system with the same corporate naming sponsor) has exclusive rights to operate bike share in their city.

Although CitiBike is contracted to a private operator, DecoBike LLC, it does generate tax revenue for the city. In contrast, all revenues on most dockless systems like LimeBike go directly to the bicycle’s operator. That’s a key issue for bike share systems in major tourist destinations such as Miami Beach.

As with most systems of its kind, CitiBike offers both a subscription as well as a pay-as-you-go model. With the subscription model, users pay either monthly or annually for membership into the system, but can then usually use bikes at no additional cost for periods of up to 30 or 60 minutes at a time.

Since most users complete their trips in less than that time, the system earns no additional revenue beyond the subscription fee. In Miami Beach, residents using the system are more likely to pay $15-25/month for one of the subscription plans, but visitors might spend up to $25-35/day for a daily pass.

Alternative options to ‘rogue’ systems

Nick Foley, Head of Product and technical co-founder of Brooklyn-based Social Bicycles, or SoBi, claims that “tourists have been a really critical part of revenue” of SoBi’s business, which manages over 30 dockless bike share systems across the country including Santa Monica’s Breeze Bike Share as well as Juice in Orlando.

The SoBi homepage

SoBi differs from its competitors in that it operates white label solutions for communities who want the advantages of dockless bike share, namely not needing to deal with the cost and upkeep of installing and maintaining docks and kiosks, while still maintaining public oversight over the system rather than ceding it to private enterprise.

This also allows communities to brand the system with their own local identity, not to mention keep all of its revenues. SoBi bikes are also equipped with integrated u-locks and need to be locked to an actual bike rack, and thus can’t be abandoned on the sidewalk the same way that other dockless bikes can.

Cities can also install specialized racks, or stations, so that they can better manage bike parking the way that traditional dock-based systems do. However, these stations are a fraction of the cost of traditional docks as all technology is built into the bike and not the station.

These stations also allow SoBi to be the only bike share system available that allows users to reserve a bike at a specific location, a welcome feature to anyone who’s ever relied on bike share for daily commuting, where morning mad dashes for bikes are the norm at transit hubs such as railway stations and ferry terminals.

According to Foley, many cities also see bike share as a critical part of their tourism infrastructure and place a high priority on setting up stations near major attractions and convention centers.

In contrast to other apps like LimeBike’s, the SoBi mobile app clearly shows the boundary lines for each system, thus making it very clear to the user where the bikes can and can’t be returned. Those boundary lines represent one of the greatest challenges facing bike share, the challenging politics of inter-municipal planning.

In West Los Angeles alone, SoBi operates separate systems for Santa Monica, Beverly Hills and UCLA, despite the fact that they’re only a few miles from each other.

According to Foley, all three systems are very successful, but this leads to as many questions as it does answers:

- Is their success limited by a hyper-localized focus that limits bike share to being intra-community rather than inter-community?

- Does this potentially open up yet another opportunity for dockless models?

- If private enterprise can introduce a bike share system that allows coverage over a wider area, then are cities willing to cede some degree of control over those systems in order to encourage cycling?

- And if it’s too difficult or expensive for cities to manage an intra-municipal program, is it just simpler to follow Seattle’s example and let the free market do it instead?

Lessons from Silicon Valley

Ironically enough, Silicon Valley itself is the perfect illustration of this.

Bay Area Bike Share (now Ford GoBike) was launched in August 2013 as a grant-funded regional pilot program by the Air Quality Management District. Rather than focusing simply on the city of San Francisco, the program aimed to serve as a “first-mile, last-mile” solution for Silicon Valley commuters as far south as San Jose, including in three smaller cities along the Peninsula; Redwood City, Palo Alto and Mountain View.

Ford GoBike locations

Those smaller cities had only a handful of docks, and most were all within a few blocks of the Caltrain station. In other words, the docks were all within short walking distance from each other, essentially rendering the system redundant. Instead of being a last-mile solution for commuters, in smaller markets like Redwood City the system was basically limited to a quarter of a mile.

With virtually no coverage to make the system worthwhile, it’s no surprise that ridership struggled. While most systems aim for a KPI of at least 1 trip per bike per day, in Palo Alto that figure was only 0.17 trips per day.

When the program was privatized, its operating partner, Motivate LLC announced that it would be expanding to the East Bay cities of Oakland, Berkeley and Emeryville at no cost to those cities. However, those other three Peninsula communities would have to now buy into the program, an offer all three cities declined.

Palo Alto, which boasts the 4th highest rate of bicycle ridership of any city in the country, began exploring other options. Just a few miles north on the Peninsula, the city of San Mateo had successfully rolled out its own SoBi-powered Bay Bike Share system after being left out of the original Bay Area Bike Share pilot.

According to Palo Alto Senior Transportation Planner Christopher Corrao, dockless was seen as a better solution for a more suburban landscape, and SoBi’s offering was the only option in the American market just one year ago.

Last October, the Palo Alto city council officially announced its plans to work with SoBi on developing a system for the city. The contract was approved by the council in February of this year with plans to launch this past summer.

However, according to Corrao, “the entire bike share landscape in this country was turned upside down seemingly overnight” within weeks of that meeting, as the dockless startups began knocking on their door with offers of no-risk, no-cost systems.

The original SoBi plan was shelved, and city planners are now closely watching developments in both neighboring Mountain View as well as Seattle to help shape a new plan that they expect to present to the council in November which will allow for 700 permits to be issued to various dockless operators.

It’s the same story in other regions where smaller suburban communities have struggled to attract interest or investment from systems designed for big cities. That’s led to opportunities for Ofo in the Boston suburbs of Chelsea and Revere who see the system as a less expensive and less complicated solution to Hubway.

Opportunities in dockless for the travel industry

The dockless model presents a whole host of opportunities for the travel industry. For travelers themselves, there’s the ability to use a single app to access bikes in a variety of markets.

Contee told tnooz that wants LimeBike to be a trusted national brand. And much like having Uber or Lyft installed on your phone means not needing to know how or where to hail a cab in a new city, having the LimeBike app installed means being able to immediately jump on a bike and ride in any market they operate, rather than dealing with registering for a new program.

With bikes often being faster than cabs in many cities, that opens up new opportunities for mobility.

Washington DC, which is threatening to surpass Portland as America’s top bicycling city, has pushed the bike sharing game even further with SoBi’s electric Jump system. The system is currently also available on an invitation-only basis in San Francisco, with plans for more cities to come online in 2018 according to Foley.

In addition to being able to more easily navigate hills, often a significant challenge somewhere like San Francisco or Seattle, riding an electric bike also means not having to get sweaty if you’re cycling to a business meeting. As perhaps the only truly unique offering in a highly commoditized marketplace, Jump is already standing out as being a cut above its competition.

The DC Jump homepage

Hotels represent another key player in the travel industry with a vested interested in bike share. Many hotels have tried to tap into the overall rice in cycling’s popularity in recent years by offering bikes as amenities to their guests, but those who do are often reminded why Steve Jobs detested moving parts.

Bicycles break down and offering them as a service means needing to repair them. Having dockless bikes available nearby means not having to worry about that, and the free-floating nature of bike share means guests don’t have to worry about returning the bikes to the hotel. They can bike to dinner when it’s still light out, but have the choice of finding an alternate way home later when it’s dark.

For all of its advantages, the dockless revolution also doesn’t necessarily signal the death of traditional bike share. Not only do communities and local officials have large degrees of political currency tied up in those systems, but they’re often integrated to the region’s transportation infrastructure.

For example, when Bay Area Bike Share rebranded to Ford GoBike this past summer, they discarded the previous system’s key fob and now instead allow access with a Clipper card, the same card commuters use on all other forms of local public transportation in the Bay Area.

And with dockless rolling out alongside Capital Bikeshare in Washington DC, Spin’s Ko claims that companies such as his “can still be complementary to Capital Bikeshare,” noting that public and private options exist for many forms of local transportation. Dockless can also be used by cities as a temporary enhancement to existing systems during periods with a large influx of visitors such as conventions and festivals.

Disrupting the disruptors

Palo Alto’s Corrao claims that one of the main reasons that he and his colleagues are closely watching what happens in Seattle is specifically because the city seems to have gotten itself in front of the dockless market, and is mandating compliance rather than allowing disruptive tech companies to make up the rules as they go along.

Simply put, rather than putting the onus on users to be on their best behavior, Seattle is putting the pressure on the operating companies to do so instead.

Whether those companies can actually do so, and for how long, remains to be seen. LimeBike and Spin are now operating fleets of 3000 bikes apiece in Seattle, with Ofo reportedly at 2000 bikes. In the end all 3 are essentially offering a commoditized service with very little to offer in terms of true differentiation.

While this competition may hopefully lead to even more innovative technologies such as Jump, the opposite may unfortunately also be true.

Those who’ve worked in the travel industry are all too familiar with the phrase, “You’re only as smart as your dumbest competitor.” Given that commoditization often results in a race to the bottom, cities such as Seattle are running the risk that the bicycle share industry could soon start to look like the airline industry, and that’s not a compliment.

Community citizenship

To their credit, most of these companies are trying to position themselves as responsible members of the corporate community. Ofo has partnered with the United Nations Development Programme to raise awareness about climate change. Spin has established the Spin Cities Project, which it claims has donated to $10,000 to various Seattle bicycle organizations such as Bike Works.

LimeBike offers the Lime Community Network, which claims to offer subsidized rides to low-income individuals, as well as options for individuals who don’t have a credit card or smartphone. And Jump’s bikes in San Francisco are currently exclusive to non-profit and community organizations in the city’s Mission and Bayview districts.

Hopefully, that sense of responsibility will lead to further investments by these companies in local bicycle infrastructure. Such investments would seem likely to pay off, as more bike lanes would lead to an increase in overall bicycle ridership, and thus more business opportunity for dockless.

With their no-cost, no-risk value proposition seemingly too much for many cities to resist, it’s clear that dockless is going to have its shot to prove itself in the American market, and that its time is now.

As for concerns that US cities may become oversaturated with for-profit bikes littering the sidewalks, LimeBike’s Contee said that he doesn’t believe that will be an issue here, pointing to his company’s strategy of asking for permission rather than forgiveness when entering new markets. “China is oversaturated because the bike companies don’t have any relationships with the local communities,” he explains. “Copying that model here simply wouldn’t work.”

Photo by Héctor Martínez on Unsplash.

![]()