Why OTA commissions are actually a steal of a deal

By cameron in Uncategorized

In the past six months I’ve written about increasing hotel brand fees (Hotel Loyalty Rate Analysis) and increasing loyalty fees (The Great Loyalty Rate Debate).

Both articles prompted some very interesting and much needed industry debate about how best to proactively manage hotel online distribution.

In what was a sea of negative OTA sentiment, I opted to take a deep dive into the issue and explore some of the lesser seen and even lesser understood facets of the hotel online distribution conundrum, in particular, the notion that direct bookings are always cheaper.

NB: This is an analysis by Peter O’Connor, professor of information systems at Essec Business School in Paris, and European online analyst for Phocuswright.

Thankfully in more recent times OTA disdain has been waning and my feeling is that it will continue to diminish over the next few years for several reasons.

Firstly, Airbnb seems to be emerging as the hotel industry’s next big disruptor, making it a convenient target for the sector’s woes.

Consumer adoption is accelerating, with one-in-five travelers already using peer-to-peer sites for business travel, and nearly half of those surveyed indicated that they have substituted what would previously probably have been a hotel stay with a homestay.

With such a large threat looming on the horizon, and a new potentially potent enemy to battle, the sector’s prior gripes about unfair OTA competition look likely to pale into insignificance.

In fact, facing a common enemy, OTAs and hotel brands are increasingly working together to unlock new potential and keep the hotel industry competitive against alternative accommodations.

OTAs are also starting to provide value in some interesting ways that the industry is not seeing from search engines, meta sites, or even chain brands. For example, Booking.com’s BookingSuite is powering brand direct sites, and thus in effect competing against itself.

Expedia’s Rev+ is making big data consumable for hoteliers, helping make revenue management practices smarter and more efficient than they’ve ever been before.

Now hoteliers have free tools to drive rate when the market supports it or occupancy with promotions and discounts when they need it most. Expedia is also signing up its customers into chain loyalty programs as well as sending qualified travelers directly to book direct channels.

And perhaps most interesting, after being an initial proponent of the anti-OTA book direct campaigns, Marriott International is itself now leveraging Expedia’s packaging technology to provide additional functionality and drive a totally new customer to their portfolio of brand.com sites.

It seems that when the chips are down, the enemy of my enemy is actually my friend.

Incremental customers?

Supporting this shift in sentiment is the fact that OTAs are typically an incremental source of customers for the travel industry.

According to Expedia, less than 0.5% of their customers search for a particular hotel brand when performing a hotel search.

A recent BDRC survey of US lodging loyalty members indicates that OTA loyalty programs have a 71% higher proportion of millennial leisure travelers and a 44% higher proportion of millennial business travelers than chain loyalty programs.

OTA program members also have a higher proportion of international travelers and frequent travelers (11+ nights per year) than hotel loyalty members. Despite hotel chain’s efforts, these customers are displaying loyalty to the OTA, not the hotel brand, but can be exploited by hotels smart enough to build synergistic relationships with their OTA partners.

With such renewed cooperation, perhaps it’s time to put another age-old fallacy to bed, that OTAs are making vast profits on the sale of hotel rooms off the back of hardworking hoteliers!

What drives OTA commissions?

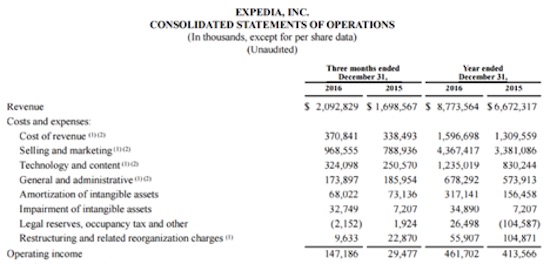

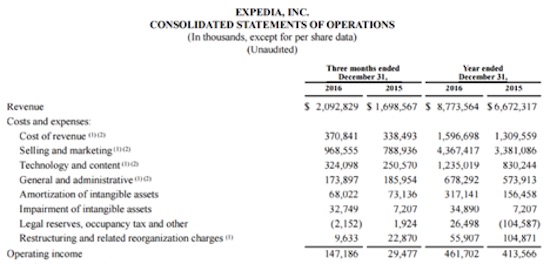

First let’s take a look at Expedia’s recent income statement:

Expedia earned $8.77Bn in revenue last year. From its annual report, it can be seen that the company primarily makes money in three ways:

- Leveraging the difference between the selling price of a travel product and the net rate at which it was provided.

- Through commissions from various travel partners.

- And through advertising revenue.

After costs and expenses, Expedia keeps $461.7MM, or about 5.3% of revenue. Expedia’s gross bookings volume (GBV) – in other words the total amount of money it collected from customers – for 2016 was $72.4Bn.

Thus, operating Income as a percentage of GBV is a paltry 0.64%. That means that for every $100 a travel product sells for on Expedia, the company is profiting by just 64 cents (down from 68 cents in 2015).

And Priceline, Inc. earned only 4.33% of GBV.

In effect, despite the widely-held perception that OTAs are making supernormal profits by scalping hotels, in reality the majority of revenues are being reinvested back into generating higher sales for the sector as a whole.

So where does commission go?

As can be seen from Expedia’s income statement, the bulk of its revenues feed the marketing expenses that ultimately end up driving demand to its hotel partners. With Expedia spending $4.4Bn per year on sales and marketing alone, that calculates to $17.75 per room night sold or $35.50 per booking assuming an average length of stay of 2 nights.

It is important to note that in the previous calculation, I am assuming the entire expense is allocated to driving lodging bookings. Although some of this amount is certainly being used to advertise airline, car rental, and destination based products, I assume these are comparatively negligible and does not detract from the overarching point I’m trying to make.

Priceline also spends more than $4Bn on performance advertising, brand advertising, and sales and marketing expenses. Such figures may seem high, but they in fact include the marketing efficiencies that OTAs get as result of their conversion expertise and economies of scale.

Trying to replicate this effort, even on a smaller scale, would quickly erode a hotel’s profits, especially as many online marketing activities have costs associated with them irrespective of whether or not they ultimately result in a converted booking.

Expedia’s financial results also reveal the extent of its technology expenditures. The company spent more than a billion dollars in technology alone in 2016, in contrast to the biggest hotel chains who don’t even break out their technology spending on their income statements.

If chains want to catch up here, they will have to either continue consolidating or increase franchise fees to support new investments, as they’ve done recently on the performance marketing side through new fee revenues.

OTA scale comes back into play here as they have millions of shoppers and customers, and every click is valuable data that allows them to optimize their traffic generation and conversion machine.

Spending on this type of innovation is what delivers hotels that far-flung guest who speaks another language, transacts in a different currency, and pays with payment methods with which they’re not familiar. And we all know that such guests stay longer, spend more and would be near impossible to attract otherwise.

Thus, in my opinion, the supposedly scandalous rates hotels pay in OTA commission are well worth it, not just because individual properties (or even most hotel chains) could not possibly replicate the efficiency of this global, multi-sector demand generation engine, but because with commissions gradually and consistently coming down, there simply isn’t a lot of profit left over.

If Expedia or Booking.com didn’t exist, there would be other companies in their place as travel facilitation has always been highly competitive and will remain so in the future.

If the entire OTA segment didn’t exist, hotels would have to rely on traditional marketing and distribution channels, which as we have discussed previously are anything but free, and in most cases, without the marketing efficiencies offered by the OTAs, often result in extremely high customer acquisition costs, limiting profitability.

With such low margins, the OTA business model only works at scale. And over the past decade we’ve seen many examples of OTAs around the world that never reached sufficient size and thus couldn’t generate the level of revenues needed to survive as a stand-alone entity in a highly competitive industry.

Even industry giant TripAdvisor’s comparatively recent move to a transactional business model with low(er) commissions has left its investors bruised, having lost about 60% of its’ peak equity value since it attempted to become an OTA.

And many others have tried, promising innovative low cost, ‘hotel-friendly’ business models with much fanfare, but all have fallen by the wayside once their initial funding ran out.

Thus, while OTA costs might to some appear high, those who really understand the realities of the hotel distribution and online marketing game are increasingly realizing that, comparatively speaking, they in fact represent outstandingly good value for the money.

By leveraging their economies of scale and global reach, they provide hotels with a cost-effective way to generate incremental bookings in a highly competitive market, all on a pay-per-performance basis.

So when are we going to stop kidding ourselves that focusing solely on direct booking is a better strategy for the hotel industry?

NB: This is an analysis by Peter O’Connor, professor of information systems at Essec Business School in Paris, and European online analyst for Phocuswright.

NB2: Hotel booking image via BigStock.

![]()