From NDC to modern dynamic air commerce

By cameron in Uncategorized

Sponsored by PROS

Three-letter acronyms – TLAs – are common-place in almost every aspect of 21st century life, and travel technology is no exception. Ever since IATA introduced its “new distribution capability”, NDC has become established as part of the industry’s shorthand.

NDC needs no introduction, but it certainly did in 2012, when IATA’s director-general-at-the-time Tony Tyler introduced the concept at IATA’s World Passenger Symposium in Abu Dhabi.

In the intervening six years, the NDC momentum has built slowly and steadily. IATA produces an annual NDC Deployment Report. This January, its report for 2017 talked about “50 live deployments”, almost double the 27 live deployments noted in the 2016 report.

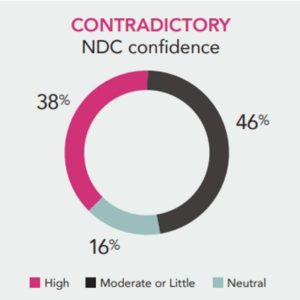

The PROS Airline Survey 2018 asked a number of airline execs for their top-line response to the theory and practice of NDC.

The results are, as we say, contradictory.

The airlines with high confidence are likely to be the ones leading the conversations – identified by IATA as “leaderboard airlines”. The large proportion with “moderate or little confidence” suggests that there is still a knowledge gap within some airline boardrooms about the potential of what NDC can do and how that potential can be realised.

NDC is a set of standards. It is a technology which opens a new world of e-commerce options for airlines. The standards are only relevant in the context of how airlines implement them and integrate them into their e-commerce and distribution strategies.

The lack of confidence may be explained by a lower readiness, rather than an active rejection.

The commercial models and business use cases for the deployment of these standards is under the control of the airlines. The deployment report notes that “80% of NDC-certified airlines have implemented both offer and order management functionalities”. One of the most significant developments in the short lifespan of NDC is the emergence of NDC Shopping, the schemas which enable airlines to distribute their products in the form of offers.

The layering of the NDC schemas means that the airline dotcom becomes the ultimate driver of the airline’s distribution strategy. The specifics of the offers sent to third parties remain within the control of the airline, giving it control over how its product is displayed, what content is made available to whom and at what price.

This article will look at three specific components of how NDC is helping airlines to create their development roadmaps – the importance of direct distribution (while not forgetting the role of indirect), the need to handle ever-increasing search volumes and the role of ancillaries.

Increasing direct (and indirect) bookings

There are many compelling reasons why airlines want to get more people booking at their airline dotcom and one of the foundational principles of NDC is that it allows airlines to present and sell their products through third parties with the same degree of control – and flexibility – they have at their owned points of sale.

Airline dotcom retailing and merchandising covers dynamic pricing, personalization, configurability, customer acquisition and retention, offer management and many more features.

Each factor above is part of how most online retailers think. The competitive landscape, margin pressure and search volumes in aviation create an even greater commercial imperative to deliver what the passenger wants. And what the passenger wants has changed dramatically. Brands such as Amazon are setting the bar in terms of consumer expectations, despite the complexity of travel far outweighing that of goods.

But the sophistication of the airline product allows for more sophisticated retailing techniques. Airlines can differentiate, personalize and tailor the offer for each distribution partner. An airline can easily test and learn pricing models and presentation techniques across origin and destination, source market, length of stay or booking window.

The foundational technology for this is a flexible shopping engine, which can take market-specific insights from an analytics engine and adjust the airline’s approach for each channel or source market.

And as is the case with Amazon, the way airlines create and distribute the offers precedes the actual purchase. It is the power of the offer that prompts the buying decision, and the true potential of NDC’s shopping capabilities lies in the airline’s ability to control the offer down to micro level.

Personalisation can come in many forms, from geo-locating the most appropriate departure airport to remembering preferences from previous bookings. Fare families, also known as branded fares, are an effective way to give the passenger the feeling of being in control of what they are buying, which is something passengers want.

By presenting a range of fares which offer optional services – priority boarding, lounge access, meal choices, baggage allowances and more – airlines can improve conversions and integrate upselling into the booking flow on the passenger’s terms.

Similarly, menu pricing also satisfies this need for passengers to feel in control. Passengers start with the seat and build their own product by adding the specific services they require for that trip.

NDC is enabling both these approaches, but that is only half the story.

Airlines can add a business rules engine into their systems which allows them to price accordingly. Yield and revenue management practices can be overlaid onto the fare family components in order for the price to be calibrated so that is appealing to the passenger while delivering the highest possible margin to the airline. Conversion optimisation techniques can also be applied in the offer creation process, backed where appropriate by the test and learn approach.

And in an NDC world, these yield management and conversion optimisation principles can be applied to the indirect channel, but controlled by the airlines.

The indirect channel has its place within many airlines’ distribution strategies. Airlines do not exist in commercial isolation from other parts of the digital travel ecosystem. The blurring of the lines between direct and indirect distribution is, to an extent, being driven by a change in approach from consumer-facing flight metasearch sites.

Metas started as a search platform with users clicking out of the meta page and onto the airline or agent page to make the booking. But now metasearch sites are starting to offer airlines “direct” or “facilitated” distribution – giving users the chance to complete their bookings within the metasearch site, using an airline-branded booking path, interface and product set which closely mirrors the experience the customer would get at the airline dotcom.

Again, it is the technical capabilities of the NDC standards which makes this possible. It is up to the airlines to make the commercial decision about the extent to which they engage with facilitated distribution as part of the overall distribution strategy. But NDC means that airlines are in control of the relationship.

The airline/metasearch dynamic is another example of how NDC standards can upgrade existing concepts as well as creating brand new revenue streams.

Most airlines are currently using non-NDC APIs to secure a direct booking presence on metas, which allows airlines to have control over what content goes to this channel. An NDC connection would enhance this because airlines would also have control over how these offers are presented.

Airlines should be trying out direct distribution on metas using the existing technology integrations. This will give them insights into how best of take advantage of the benefits that an NDC connection will bring.

Of note when talking about metasearch is the fact that many of the world’s leading metas are owned or majority owned by the OTAs – Booking Holdings owns Kayak and Momondo, Expedia Group has a majority interest in Trivago, Ctrip owns Skyscanner. The blurring of the lines between OTAs and metas will change consumer patterns but it will also have an impact on airlines, reinforcing the imperative for airlines to be in absolute control of their inventory, which distribution channels it is shared with and on what commercial terms

Elsewhere, airlines are watching with interest the efforts major hotel chains are putting into direct bookings, from above-the-line campaigns telling guests to “stop clicking around” to offering a discount to anyone joining the loyalty scheme. Airline dotcoms could see a benefit to their direct booking strategy, courtesy of their hotel peers.

A better brand dotcom can foster a better indirect presence because, in the NDC world, the airline dictates how third parties sell its inventory.

Handling the search volumes

There is more to search than Google, although its dominant global market share means that is the inevitable reference point. It is circumspect about revealing the volume of queries it handles. In 2016, specialist industry news service SearchEngineLand reported that Google was handling two trillion search queries a year.

The volume of internet traffic which airline systems handle has grown in synch with the overall growth in search. Airline systems behind the home page must handle traffic from brand dotcoms, GDSs, OTAs metas, aggregators, tour operators etc.

Underpinning this is an organic growth in the sheer volume of air traffic, a growth profile which shows no sign of slowing down. In 2012 the total scheduled passengers taking to the air across IATA member airlines was three billion – provisional figures for 2017 put this number at more than four billion. But by 2036 IATA believes the figure will reach 7.6 billion.

Airlines also need to ensure that their systems are fit for purpose in terms of how travelers search shop and buy. The contemporary path to purchase is complex. A report from Expedia Media Solutions and comScore, published late 2016 found that “American, British, and Canadian travelers visit 120 to 160 travel sites before booking a trip”.

A more recent study from Sojern opted for a different breakdown, by traveler type rather than nationality, and suggested that the idea of the average traveler was misleading – each trip and traveler is unique. It looked at touchpoints rather than visits and was able to see how often different types of traveler engaged with airline sites.

The complex path to purchase means, put simply, airlines need to be able to not only handle more traffic but also respond more quickly and accurately regardless of the channel. Airlines also need to offer passengers search options other than the traditional origin and departure parameters – flexible departure dates, defined budgets, map-based searches. Technology facilitates innovative search and guarantees speed and accuracy of results across all distribution and marketing channels.

Passengers are not aware or interested in the complexities of airline IT. They expect sub-second response times to their specific request and expect that response to be accurate. Time is the new currency – airlines are part of the digital retail world where customers demand almost instant answers.

Ancillaries

The theory and practice of ancillary revenues has come a long way since IdeaWorks released its first-ever “Ancillary Revenue Yearbook” in 2008. In dollar terms, the growth has been phenomenal, even factoring in forex fluctuations and changes to the sample size and methodology. The 2008 report referenced 2006 data and calculated that ancillary revenues that year were worth $2.29 billion. Last November its estimate for 2017 was $82.2 billion.

In an NDC context, the ability for airlines to distribute their content to third parties in the same way as they sell on their brand dotcoms means that the growth profile for ancillary revenues becomes even more compelling as the additional indirect distribution channels open up. Traditionally the airlines with the greatest proportion of direct bookings, such as the low-cost carriers, were generating the most ancillary revenues. Now, even the most upmarket of full-service carriers offer passengers ancillary options.

The ability to upsell a range of ancillary products and services to passengers across multiple devices and touchpoints is another way for airlines to square the circle between giving passengers what they want, when they want it, at the price they want pay, while optimising their own revenues.

NDC allows for a single view of the offer – the fare, the available seat and the ancillaries. With the functionality in place, airlines have control in deciding whether to adopt this approach.

High pricing flexibility enables airlines to optimise their revenue from each passenger, while rich content provides a superior shopping experience for passengers at the brand dotcom and indirect points of sale. A lesson from the wider e-commerce world – the eBays, Amazons and Netflixs of the world – is that a superior shopping experience is one of the most effective ways to garner customer loyalty. These digitally native brands have defined the frictionless online shopping experience, and airlines must match this, despite their product being materially more complicated.

The complexity for carriers comes in deciding and implementing the commercial models for their own specific requirements.

The PROS Airline Survey 2018 asked airlines to outline what aspects of offer management (shopping) were the most challenging. The cross-section of responses, with no dominant answer, is a sign that the airline industry has a rich and diverse approach.

Conclusion

NDC is here – it is happening. It is being embraced by the tech giants and nimble startups alike. It is only relevant in the context of what it enables airlines to do, the additional revenues it can generate and the benefits it brings to passengers. It has evolved, and will continue to evolve, in isolation and in how it connects to other existing and yet to be devised standards. There will be some twists and turns along the way, and the wider world in which aviation exists is not static.

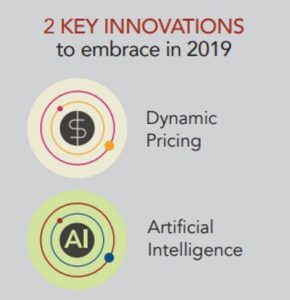

The PROS Airline Survey 2018 identified two components which airline execs expect to dominate the NDC agenda in 2019 – dynamic pricing and artificial intelligence.

The entry of dynamic pricing into the airline industry commercial lexicon is facilitated by NDC, while artificial intelligence is part of the wider e-commerce world in which airlines exists. By combining the two, forward-thinking airlines can move on from “offer creation” to “offer optimisation”.

While some are still considering the commercial model behind offer creation, others are already planning to personalize the offer, using dynamic pricing and AI, in real-time, across its chosen distribution channels and partners.

Offer optimisation is also where NDC is heading and is a concrete example of how the new distribution space is helping airlines find their own path to profitability.

This article from PROS appears as part of the tnooz sponsored content initiative.

![]()